The Steel Rush Marissa Potasiak

Marilyn S. Johnson is the History

Department Chair and a professor at Boston College, teaching courses on social

movements, working-class history, and the American West. She received

her bachelor degree in History at Stanford and her Ph.D. in History at New

York University.

She has written four other books and received the Sierra Prize from the Western

Association of Women Historians for The Second Gold

Rush.

Marilynn S. Johnson��s book, The

Second Gold Rush: Oakland and the East

Bay in World War II, provides an

in-depth account of the effects of World War II on the East

Bay region of California,

allowing her to uncover the human story of wartime migration and urban growth.

This detailed focus of a specific community reveals the amazing social and

cultural changes this region experienced �V changes Johnson sees as ��the most

enduring legacy of World War II.��1

Even

before the boom of World War II, Oakland

was a major city, topping San Francisco

as the East Bay��s

business, industrial, and financial center. But even though Oakland

and its nearby neighbor Richmond

housed factories from giants such as Standard Oil and General Motors, these

cities still maintained a quiet, small-town feel. During the war, old time

resident��s nostalgically remembered a place where ��different ethnic and racial

groups lived alongside on another�� in a ��fluid and tolerant social climate.��

This stable environment �V with a relatively small immigrant population �V is

what old-timers longed for during the war years, with their formerly homogenous

communities replaced with striking, and to them terrifying, diversity. After Pearl

Harbor, the government gave billions of dollars in federal

subsidies to industrialists like Henry Kaiser, creating an overnight defense

boom in the East Bay.

World War II was the gold rush of the twentieth century and ��unlike the earlier

boom...the federal government now played a key role in directing and

facilitating the flow of migration.��2 Shipbuilding

was the major industry, with 150,000 people working in East

Bay shipyards.3

The population of Oakland

increased by 500,000 people from 1940 to 1945, with the immigrant population up

67.3%. Most were out-of-state settlers from Texas,

Arkansas, Oklahoma,

and Louisiana. These

defense migrants �V eager for the high wages of Californian shipyards �V

contained majorities of women, young people, and African Americans.

These groups enjoyed economic opportunities unattainable in their home states,

but their presence also created new biases among former residents.

The war transformed both shipbuilding and

the treatment of shipyard labor. New building techniques such as

pre-fabrication (building the individual parts of a ship separately, before

assembly) transformed ��skilled trades into assembly-line production��, causing

anger among old-time workers and their unions at the de-skilling

of their jobs.4 The old-timers took out

their anger on the new migrant workers �V African Americans, women, and

southerners. Old-timers felt these migrants were undeserving of their new,

high-paying jobs and were frustrated with relative ease at which they moved up

into semi-skilled positions. But these groups could never advance to

supervisory positions, were placed in segregated workspaces, and were

constantly subjected to racial and sexual stereotypes; African Americans got

lower-paying, physically demanding jobs and women were often accused of

prostitution. Unions offered little help to these workers, so management

stepped in; Kaiser offered his workers ��corporate welfare�� �V healthcare

services, childcare, and leisure activities. Despite this help from management,

migrants faced their biggest obstacle finding housing. The private sector

proved unable to provide enough housing for the thousands of new war workers,

forcing thousands of migrants to share tiny houses with extended family, move

into decaying trailer parks, or simply sleep on the streets. When the federal

government finally stepped in, they ��introduced new forms of federally

sanctioned racial segregation�� creating ��shipyard ghettos�� that isolated

old-time residents from newcomers and African Americans from whites.5 This ��patchwork�� segregation cemented

post-war neighborhood settlement, creating lasting racial tensions. In total,

30,000 public housing units were built for 90,000 East

Bay workers, mass-produced houses

made from cheap materials, often placed in undesirable locations.

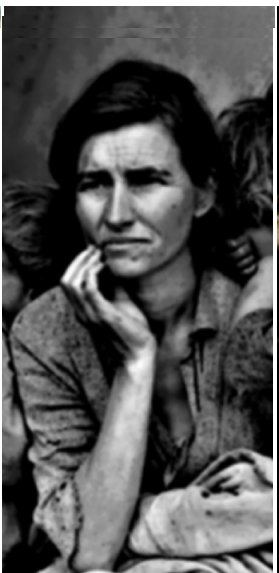

Migrants

relied heavily on family connections to adjust to their new lives. The family

was the main source of support because ��long hours, high turnover, and extreme

social diversity all served to hinder the growth of a common culture in war

housing areas.��6 Overcrowding, new roles

for women, and new power for youth caused these families extreme stress. Men

felt threatened by the loss of their position as breadwinner and feared marital

infidelity in the workplace �V both divorce and marriage rates increased during

World War II. Young people became more independent �V often making more money

than their parents �V causing a generational conflict between parents and

children. Although they all dealt with common problems, migrants couldn��t lean

on the migrant community for support because neighbors constantly moved and

migrants worked varied shifts. Neighbors never had a chance to get to know one

another. But there was a sense of geographical unity among some migrants,

especially southerners. They brought their evangelical religion and popularized

country and blues music �V both having a lasting impact on Californian culture.

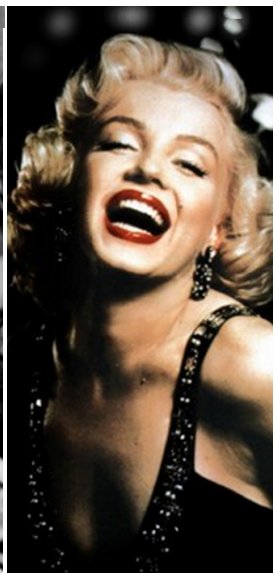

Migrants also had a large impact on the cities they surrounded. These boomtowns

��provided new social opportunities and freedom...for the migrants, blacks, and

women who enjoyed new defense earnings��, a transformation that ��shocked the

sensibilities of the prewar middle class.��7

Retail businesses earned five times the amount they earned before the war, with

migrants buying previously unattainable consumer goods �V even fur coats were

within their reach. Old timers felt invaded by wealth-flaunting migrants, who

seem to bring with them street peddlers, gambling, prostitution, movie

theatres, and bars. Blaming the migrants for ��ruining�� their cities, city

governments targeted migrants for arrests, taxed theatres and jukeboxes,

allowed segregated stores, and controlled female access to bars, dancehalls,

and other public spaces. Migrants gained new economic freedoms but were subject

to persecution and injustice.

East

Bay city governments were dominated by conservative, business

elites before and during the war. However the war ��presented an opportunity to

challenge the political status quo�� and ��a coalition of labor, black, and other

progressive forces coalesced during the war and would become a major contender

in the...postwar era.��8 City governments

promised to enact a series of public works projects after the war, including

much needed road, sewer, school, and hospital repair. But these promises failed

to materialize and unemployment increased dramatically after the war �V

especially for women and African Americans. Additionally, the migrants didn��t

leave East Bay

cities �V as conservative city officials had hoped �V instead, more continued to

come. All these factors gave women, African Americans, labor, returning

veterans, and progressive forces an opportunity to change city politics, enacting

a general strike in 1946 and electing new board members to the city council.

This victory was short-lived however, as returning prosperity and the fear of

communism discredited this coalition. The most crucial issue of the postwar

years was public housing. Conservatives were eager to see public housing

destroyed, hoping to clean their cities of blight and squalor and attract

private investment. In the early 1950s, cities like Richmond

��evicted thousands of minority and low-income tenants, sowing the seeds of

racial discontent that would plague Richmond

and other East Bay

cities for decades.��9 Cities evicted

public housing tenants based on race and, in racist real estate market, forced

African Americans to move into already overcrowded black neighborhoods. The

lack of available, decent housing caused overwhelming frustration and anger in

the African American community; the issue was the underlying cause of the race

riots of the 1960s. Racist postwar housing policies created animosities that

forever changed the East Bay.

Throughout

her book, Johnson claims World War II was a second gold rush for the East Bay,

not only economically, but also in the social diversity it brought to the

region. The Bay Area was the nation��s number one shipbuilding center, with over

5 billion dollars in federal contracts.10 The shipyards�� high wages �V the highest of any shipyard

center in the country �V created overnight boomtowns, just as the gold rush had

in 1849. And like the earlier gold rush, the population drew dramatically. In a

region where immigrants were previously ethnic whites �V Italians, Irishmen,

Germans, and Scandinavians �V the East

Bay now had a much larger

population of African Americans and southerners. Migrants infused the region

with women and young people, reversing the previous majority of older men.

World War II boomtowns were just as energetic as those in the gold rush, with

their bars, movie theatres, and crowded shopping centers. Like gold miners who

struck it rich, defense workers seemed to have more money they than knew what

to do with, creating a jovial and some what reckless environment. Servicemen

waiting for assignment further energized the boomtowns; knowing they may not

come home alive, their only focus was to have fun. Just as important to Johnson��s

thesis are the larger racial effects of the war. She argues early federal

segregation of migrant housing forever changed the East Bay; minorities were

isolated in sub-standard conditions, creating divisions and biases that would

remain for decades. African Americans replaced Asians, the group that had been

abused in the first gold rush, as the source of racial prejudice amongst East

Bay residents. Decades of injustice, especially in housing, ��finally exploded

in the mid-1960s�� when ��black rioters responded not only to immediate civil

rights issues but to a long history of racial oppression.��11

In many ways, World War II was a twentieth century gold rush for the East

Bay.

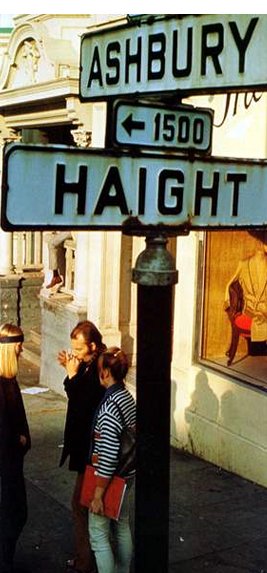

Johnson

reveals herself several times in her book as liberal-leaning historian, focusing

on women and minorities in the tradition of New Left historiography. Published

in 1993, in

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, The Second Gold Rush was published with

the help of a university known for being liberal. In fact, the region she covers

in the book is today one of the most liberal areas of the country and the

progressive-minded climate must have had some influence on her writing. But

it��s the subjects of her book that show her to be a New Left historian. Writers

who grew up in the sixties were confronted with the issues of race and poverty

and New Left historians focused on the common person��s experience to understand

how society became this way. A majority of Johnson��s book deals with the life

of the common person, only a few times mentioning specific names and prominent

people. Her main focus on migrants, minorities, and women reflect the New Left

emphasis on pluralism. Johnson also unfavorably depicts the conservative

business leaders who ran East Bay

cities, saying ��conservative rule�� resulted in the ��callous treatment of black migrants.��12 And unlike conservatives who

dislike government interference on a local level, Johnson takes no issue with

federal involvement during World War II; she just takes issue with the racial

segregation they employed. Overall, Johnson��s emphasis on everyday life, her

unfavorable judgments of conservatives, and her focus on women and African

Americans make her book a New Left history of Oakland and the East Bay in World

War II.

Literary

criticisms of The Second Gold Rush are generally favorable �V praising Johnson��s

focus on the ��human dimension�� of wartime migration and her varied sources. University

of California Press commends

Johnson for her ��wide-ranging�� sources that ��include shipyard records, labor histories,

police reports, and interviews.��13 These

diverse sources allow Johnson to show the effects of the war years from many

different points of view, as well as providing evidence to support her thesis.

A review in the history periodical Choice also praises the book��s many

photographs, maps, and tables that give an unaltered sense of life in World War

II. Choice reviewer D.F. Anderson believes ��Johnson

provides as excellent case study of the ��human dimension�� of wartime western

urban America�� �V a dimension that is often lost in larger, more general studies.14 The major criticism of Johnson��s work

is she ��tends to overstate the discontinuity between wartime and prewar

society��, meaning she doesn��t address the connection between prewar economic

and social forces and what happened during the war as well as she needed to.15 But as a whole, The Second Gold Rush is

��recommended for all college and university collections�� for it��s multi-layered

analysis of the unrecognized masses of World War II migration.16

Johnson

effectively proves her thesis that World War II was a second gold rush for the

East Bay and adeptly explains the complex racial, social, and cultural elements

of East Bay society. But it��s Johnson��s analysis of the data from this period

that really makes this book meaningful. Often showing the hidden meaning behind

the statistics, Johnson shows how city officials and old-timers manipulated

information for their own use. For example, in 1943 officials in Oakland

and Richmond declared a ��Crime

Wave�� caused by the new, immoral migrants.17

Police records do in fact show a rise in crime but this is only part of the

story. Johnson explains that these numbers went up for many reasons: the

population increased, the numbers of young, at risk men increased, and police

made more arrests, targeting migrants for minor offenses such as vagrancy. In

fact, the number of murders actually dropped during the war years, showing

violent crime had not increased. Johnson shows that city officials used the

fear of a ��Crime Wave�� as an excuse to control migrants and to convince the

federal government to grant them more funds. Throughout the book, Johnson

provides impressive analysis showing the complexities of migrant, old-timer

relations. It��s this analytical skill that makes A Second Gold Rush a

worthwhile read.

Johnson

also shows how the events in East Bay related to the rest of the country.

Cities along the west coast like Oakland

and Richmond ��grew at the expense

of those in the Northeast.��18 Small towns

across the country disappeared as people who had long suffered during the

depression went west for jobs. California was deeply influenced by the cultures

these migrants brought with them, from evangelical religion to blues music. The

actions of the government in Washington D.C. also had an enormous impact on the

East Bay. After the United States entered the war, the federal government gave

billions of dollars in contracts to East Bay shipyards, transforming the

economy overnight. The federal government also helped encourage migration from

the rest of the country to California, making them the source for much of the

East Bay��s new diversity. Just like the rest of the country, the East Bay

citizens dealt with the stresses of wartime life �V rationing, women in the

workplace, and war-related deaths. The East Bay experienced World War II along

with the rest of the country, but they were affected in some distinctive ways.

Everything

that happened in the East Bay,

and California in general, was on

a larger, more dramatic scale. Hundreds of thousands of people migrated to ��one

of the nation��s largest shipbuilding centers��19

to earn the highest wages offered in the country. Californian defense

industries produced a majority of the nation��s naval ships and aircraft and

served as the launching point for the war in the Pacific. California arguably

became the most diverse state in the country, with African Americans and

southerners mixed with California��s existing minorities. This mix provided a

window into American racial conflicts and showed how easily prejudices can rip

apart a region. The war firmly established California as central to America��s

economy and the racial conflicts that resulted showed the desperate need for

America to destroy its racial divides.

In

conclusion, Johnson��s account of the effects of World War II on the East Bay

goes where few World War II histories have gone �V into the complex, chaotic

lives of defense migrant workers. They had a lasting effect on the region,

creating thriving boomtowns, ��transforming social relations and cultural life��,

and enduring the wrath of long-time residents unwilling to change.20

The people who built the ships that helped win the war uncovered the deep

biases Americans held against outsiders, biases that would take decades to

eradicate.

1. 25-26; Johnson, Marilynn S. The Second Gold Rush: Oakland

and the East Bay

in World War II. Berkeley and Los

Angeles: University

of California Press, 1993 2.

2. Johnson, Marilynn S. 25-26.

3. Johnson, Marilynn S. 30.

4. Johnson, Marilynn S. 33.

5. Johnson, Marilynn S. 33, 41.

6. Johnson, Marilynn S. 60-61.

7. Johnson, Marilynn S. 83.

8. Johnson, Marilynn S. 114.

9. Johnson, Marilynn S. 143.

10. Johnson, Marilynn S. 185.

11. Johnson, Marilynn S. 209.

12. Johnson, Marilynn S. 32.

13. Johnson, Marilynn S. 232.

14. Johnson, Marilynn S. 233.

15. University of California Press. Preface. The Second Gold Rush: Oakland

and the East Bay

in World War II. Berkeley and Los

Angeles: University

of California Press, 1993.

16. Anderson, D.F. ��Social & Behavioral Sciences / History, Geography

& Area Studies / North America�� Choice Jan. 1987.

Jul. 1994. May 29, 2008.

<http://www.cro2.org/default.aspx?page=reviewdisplay&pid=1911792>

17. Anderson, D.F. <http://www.cro2.org/default.aspx?page=reviewdisplay&pid=1911792>

18. Anderson, D.F.

19. Johnson, Marilynn S. 153.

20. Johnson, Marilynn S. 3.

21. Johnson, Marilynn S. 4.

22. Johnson, Marilynn S. 2.